All About the English Major

I knew that I wanted to study English when I came to Dartmouth. I love writing and reading of all kinds. In high school, I was that kid who not only did all the required reading, but read the introduction, footnotes, and the Wikipedia page for the book to boot.

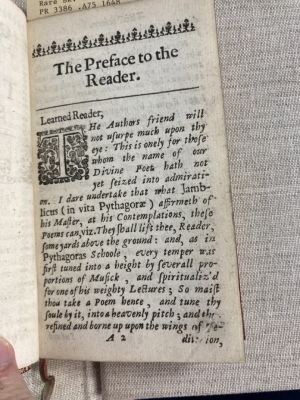

But college-level English studies are far more varied and interesting than I could've predicted. Professors and students here work with everything from Old English epics and early modern translations of Latin texts to social media and memes. Some of us work primarily with texts in the "canon," while others spend their time analyzing letters, diaries, emails, blog posts, newspaper articles, advertisements, and forgotten pulp novels.

Nor did I realize how much I still had to learn. I came into Dartmouth thinking my reading, writing, and critical thinking skills were at their peak. In high school, I'd easily gotten high grades in humanities classes, and I didn't see why it would be any different here.

My sophomore fall, I took a class called Media and Monstrosity. I liked it—the materials we were working with, a mixture of canonical texts like Dracula, Weimar cinema, Victorian advertisements, and Naturalist pulp fiction in translation, were undoubtedly engaging. I came into Dartmouth absolutely despising the Victorian era, but I began to love it.

Then I got my first essay back, graded. It, uh, wasn't ideal.

I'm not a grade-grubber. One of the most valuable things Dartmouth can teach you is that you're not going to be the best at everything, and I learned this lesson early on with a very below-the-median grade in a chemistry class. It wasn't the grade that I minded. It was that I considered myself an excellent writer and reader, and clearly, the professor thought I could improve. I went to his office hours to figure out what, exactly, I needed to be doing differently.

First, he said I was a good writer. I grinned. Obviously. Then he said, "You didn't understand the assigned reading."

What?! I protested that I had read it and understood it—it was in my native language, after all. How could I not understand something written in English?

"I'm sure you read it, Kennedy—but you didn't understand it."

At first, I was fuming. Then I realized he was right. The material in question—a brief but complex essay called "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" by Walter Benjamin—was not exactly an easy read. I'd skimmed it, failed to grasp core concepts, and brushed it off as not well-written. My mistake was assuming that good writing meant easily digestible writing. What Benjamin and many other excellent writers do is not accessible through skimming because they are packing meaning into each sentence. We're used to grabbing a sentence with our eyes and immediately understanding it because that sells and communicates. If someone's trying to advertise to you, or warn you not to use a hair dryer in the bathtub, they'll do that in as easily readable a manner as possible. But if someone's leveraging a complex series of ideas into an argument, they will have to write in a complex and interlocking manner.

I read "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" again. I took detailed notes. If I didn't understand a sentence, I read it again. I went slowly. I flipped back and forth. I made a goofy-looking diagram. And when I went to class, I was prepared to explicate the entire thing. Moreover, I realized how wrong I'd been. Walter Benjamin wasn't a poor writer. He was an incredible writer and thinker, and I needed to put forth the effort his work deserved to understand it fully.

Thanks to that professor—who is now my advisor—and so many others in the department, my reading and writing skills have grown beyond what I thought possible. I have learned research techniques alongside my exploration of literature. I have become not only better at critical thinking and reasoning, but at expressing my logic in writing. In the English department, I don't just get to read books. I've learned invaluable skills while doing what I love—taking literature seriously.

The Dartmouth English department has a lot going for it—our libraries, the excellent students in the major, and our beautiful department building, Sanborn House. But the best thing about the department is our faculty. Professor Tanoukhi has led some of the most intense and fascinating class discussions I've ever been in. Professor Dever is a cutting-edge researcher working on underrecognized Victorian female poets, and she is an incredibly supportive instructor (and boss!). Professor Edmonson encourages critical thinking and invested class discussion. And my advisor, Professor McCann, has undoubtedly made me and lots of other students much better writers and thinkers. These and many more professors give their time generously. They make the department what it is.