Language Revitalization: Heritage Languages at Dartmouth

I've always had a vested interest in languages. From birth, I grew up hearing my quadrilingual mom speak to her friends and family in rapid Filipino languages and remember using my dad's computer to learn basic French and Spanish as a four-year-old. This love for language never died, and I was inspired to come to a place like Dartmouth which not only featured so many languages in its curriculum, but also where enrolled students speak languages that span the world.

Only a few centuries ago, preceding the Age of Colonization, the world was much more linguistically diverse. Many languages spoken across the Americas and the Pacific have since suffered greatly if have not gone extinct altogether (meaning all of its speakers die out). Since coming to Dartmouth and taking a class within both the Linguistics and Native American Studies departments, I've started to explore and research the topic of language revitalization -- the process by which linguists, the government, and educators work together to revive languages by increasing their use. In a world where English has become overwhelmingly spoken worldwide, many smaller languages are being lost to history or, in extreme cases, disappearing with little trace.

There are numerous indigenous languages spoken by the Native communities nationwide in the continental United States, Alaska, and in Hawaiʻi. Among myself and my Native friends, the experiences learning our heritage languages (languages spoken by our ancestors) range from having taken ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian) and Choctaw in high school as an elective or class to hearing the language spoken by family members and elders within the community.

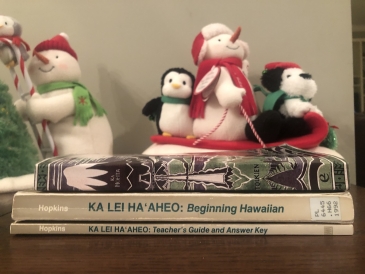

In the summer prior to my arrival at Dartmouth, I started to learn Hawaiian. My experience was largely constrained to Duolingo and random websites, but I was inspired to study much more vigorously after learning that Dartmouth offers a special path for students who are interested in using their heritage languages to satisfy the Dartmouth Language Requirement.

Because Dartmouth doesn't offer classes in languages like Hawaiian, Mohawk, or Tlingit, or any Indigenous language of the United States, I was able to reach out to Professor Nicholas Reo, a Professor within the Native American Studies Department (NAS) and himself a student of the Ojibwe Language, his heritage language. I attended an open house with Professor Reo in the Homelands Studio, a space for students interested in the intersection between indigenous stewardship and environmental studies. He laid out several options for me that enabled me to choose Hawaiian as the language to satisfy Dartmouth's Language Requirement. I plan on continuing to self-study the language in my free time before taking an Independent Study within NAS during the Spring Term to structure an individualized class for myself to attain the conversational fluency necessary to meet Dartmouth's requirement.

As part of my planned Linguistics major, additional language classes are required beyond satisfying the language requirement. Curious, I emailed the Department Chair of the Linguistics department, Professor James Stanford, and not only was he incredibly receptive to the idea of my using Hawaiian, but said if I was interested in taking more advanced classes in the future to satisfy additional major requirements that this was a definite possibility and he'd love to speak about it later if I ever decide on that course of action.

The United Nations declared 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages, and I think it's super fitting that it should also mark my arrival at a place like Dartmouth with so many options to Indigenize my academic career. Choosing Hawaiian over Spanish or French is an actively more difficult path necessitating more individual exertion, but I wouldn't have it any other way. It's an incomparably redeeming when you're actively learning a language of your ancestors with (moderate) success on occasion, and every new word inspires me to keep going.

Dartmouth allowing Indigenous students to use their heritage languages as a way to satisfy an academic requirement has been a longstanding tradition, but to have new rules and guidelines in place that offer structure to those of us who don't already speak our heritage languages to eventually arrive at that place is a very humbling gift that I couldn't be happier to embrace. Aloha nō until next time!