In each issue of 3D, we turn this page over to a current student to reflect on their Dartmouth experience—or, to put it another way: to share how they've been "walking the walk." A government major and psychology minor from Charlotte, NC, Chelsea-Starr Jones '23 is an ambassador to prospective students as a senior fellow in the office of admissions. She's also been a tour guide, a research assistant at Dartmouth Engineering, and currently serves as president of Kappa Kappa Gamma Sorority at Dartmouth. After graduation, she'll begin her career with a job in healthcare consulting. As she nears the conclusion of her undergraduate experience, Chelsea-Star reflects on being a leader of a Greek organization.

When I arrived on the Dartmouth campus, the idea of Greek life conjured up images of a huge mansion filled with wealthy, white, blonde women who all come from similar backgrounds, dress and sound alike, and enjoy the same things. Essentially, I thought of someone who is the antithesis of me. So, people often ask me—and I often ask myself—how I ended up as the president of a sorority at Dartmouth.

Greek life is, for lack of a better word, an enigma. The phrase is used to describe fraternities and sororities, also known as "Greek houses," organizations of men, women, and/or non-binary individuals who come together for social, academic, or philanthropic reasons. The history of Greek life in the United States is riddled with instances of racism, sexism, classism, nepotism, and hazing. But for many, Greek life can be a way of finding community on a college campus. In other words, fraternities and sororities are complicated organizations and difficult to paint with a broad brush.

Dartmouth has local sororities and fraternities, national Panhellenic Greek organizations, historically Black Greek organizations, gender-inclusive Greek houses, and multicultural Greek houses that students can join beginning in sophomore year.

My sophomore winter, I underwent rush (the process by which many Greek houses recruit new members) virtually because of the pandemic. I spent that time wondering what I wanted out of a Greek experience, which house I wanted to join, and if I really fit in anywhere. As the end of rush neared, I attended an event where the president of what would become my future sorority spoke to all the potential new members. Much to my surprise, she was a dark-skinned Black woman who spoke with confidence and kindness. I remember sitting in awe of this woman who was doing what I subconsciously didn't think was possible or allowed: taking up space in a place that wasn't made for her.

As someone who has grown up in spaces that weren't made for me—a low-income, first-generation American in private schools surrounded by generationally wealthy white peers—I've survived by making myself as palatable as possible. I have said what needed to be said, showed "star power" in all the acceptable ways, and otherwise kept myself as small and nondisruptive as I could; I stayed in my place. But here was this Black president who wasn't limiting herself to the shadows, to what was easy or expected of her. I found inspiration in her that led me to join that sorority and her family.

That woman became a mentor for me and later empowered me to run for the presidency of our sorority. My rationale mirrored what I found inspirational when I first met her: I wanted to be a voice for those women who feel marginalized, to show them that taking up space is not only allowed, it's encouraged. As an exercise in preparing myself for the real world where spaces are not made for me and as a participant in a legacy of women who live fully, being a leader in the Greek community has been fulfilling—and, hopefully, will impact generations of women after me.

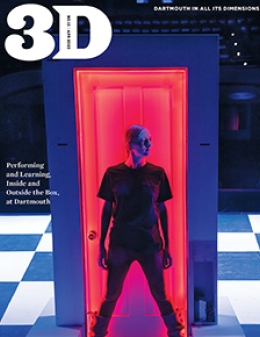

Photograph by Don Hamerman