Advocating for Energy Equity

Last year Solange Acosta-Rodriguez '24, a member of the Energy Justice Clinic, traveled to southern Chile to meet members of the Indigenous Mapuche-Williche community. "They believe that their ancestors' souls flow through the rivers of their land," she says. The Mapuche have been engaged in a protracted dispute over their spiritual and territorial land rights with Statkraft, a Norwegian state-owned company that acquired rights to build dams on those rivers for hydropower projects.

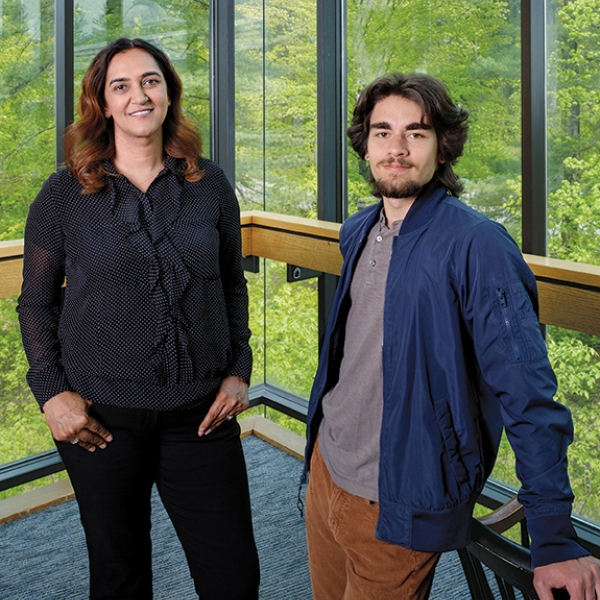

The clinic, founded by anthropology professor Maron Greenleaf and post-doctoral researcher Sarah Kelly in November 2021, gives undergraduates hands-on experience in supporting equitable energy transitions. It was created with the support of the Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society, which was founded in 2016 to leverage the College's strengths in interdisciplinary teaching and learning, engineering, business, and sustainability to provide solutions to critical energy problems across the globe.

"In this generation," says Greenleaf, "there's a sense of urgency about the climate crisis. There's a real sense of 'We need to do something.' Participating in the clinic is a way to take what we learn in a class like Environmental Justice about inequality in the world and try to do something about it."

Miami resident Acosta-Rodriguez, who is majoring in geography and environmental studies and worked on the Appalachian Trail this summer, accompanied Kelly to Chile. She then joined a small delegation from the Mapuche-Williche community who traveled to Norway to press their case. She was gratified that members of the Mapuche "mentioned how important it was to feel like they were heard—like they aren't just voices crying out in the desert."

Closer to home, the Energy Justice Clinic continues to work on Community Choice Aggregation, helping people in towns including Hanover decide whether to join the Community Power Coalition of New Hampshire, which enables municipalities to collectively purchase electricity that is more renewable—and less expensive. Clinic members also partner with Vermont nonprofit Cover Home Repair to help Upper Valley residents weatherize their homes.

"We've had the fortune to attract students who want to get engaged in real-life issues around energy justice, who are interested in really relating to communities, and also are quite passionate and driven in their work," Kelly says.

Deluges and Drought

As a first-year student, Christopher Picard '23 took a class called How the Earth Works. "Toward the end of the class we started talking a bit more about climate," Picard recalls. He learned that a student in geography professor Jonathan Winter's Applied Hydroclimatology Group had done some regional climate models. That sparked Picard's interest, and he lined up a grant to dig into the data, working remotely over the pandemic's first summer. He then continued to work as a research assistant with Winter on the project.

Their study, published this spring, predicted that extreme precipitation in the Northeast will increase 52 percent by 2099. That has implications for flooding, bridge stability, and agriculture, Picard says. The study also projected that extreme precipitation in the Northeast's winters will increase by 109 percent.

The study, with Picard as lead author, appeared in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change and was featured in The Boston Globe and The Christian Science Monitor. "I just wanted a summer job, and it ended up kind of changing my whole trajectory," he says. "Undergraduate research has been the most impactful part of my time at Dartmouth. If you want to get into it, it's easy. Just come up with a good idea. The professors get excited and there's tons of funding." Picard, who did a senior thesis on glacier science in Greenland based on remote sensing by satellites that monitor changes in earth processes, is now a graduate student at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

In his class on Climate Change and the Future of Agriculture, Professor Winter's students also investigate how warming temperatures will change crop yields. Using corn plants grown in the greenhouse at the Class of 1978 Life Sciences Center, his research assistants test their tolerance to differing levels of drought. Winter says his research often overlaps with his teaching. "Students have such great questions. At the end of the term I'm always saying, 'If you're interested in research, in climate and sustainability, you should let me know.'"