Orienting to Dartmouth Through the Orozco Mural

Posted on September 14, 2018 by Hannah Silverstein

The Class of ’22 “reads” the Orozco Mural as a shared academic experience.

When the Class of 2022 arrived on campus for their weeklong New Student Orientation, they were introduced to College life—from the house community system to course registration to the myriad extracurricular opportunities open to them.

Every year, a central part of this orientation—the Shared Academic Experience—has the entire class read a book, selected by a member of the faculty, over the summer. In the past, this text has been a novel or a work of nonfiction. But this year, Associate Professor of Art History Mary Coffey—an expert on Mexican muralism and U.S. and Latin American art—asked the ’22s to read not a book, but a painting: specifically, The Epic of American Civilization, José Clemente Orozco’s monumental mural, which he painted on the walls of the Dartmouth Library’s Baker-Berry Library reserve reading room between 1932 and 1934.

Choosing the Orozco mural—which in 2012 was named a National Historic Landmark—as a shared text “presented a couple of opportunities and a couple of challenges,” Coffey says.

One opportunity: The mural is a perfect tool to spark discussion about some of the most important issues of our time.

“My framing question is why was there a Mexican artist here doing this in the 1930s, and what was he trying to his say to his U.S.-American audience? He’s challenging U.S.-American conceptions of history, particularly those that rest on a Manifest Destiny ideology,” Coffey says.

“That’s relevant to us today, because it bears on the ways we imagine a difference between, say, ‘Hispano’ and ‘Anglo’ America or the U.S. and Mexico, how we understand how that historical border is created, how we understand the relationship between settler populations and indigenous peoples, and so on. This is a rich text for challenging and problematizing some of our received understandings of our own identity, our own history, and our geographical boundaries. It’s also an incredible political resource for people in the present who are fighting some of these battles.”

One challenge: Students couldn’t purchase or borrow a copy of the mural to read over the summer, the way they could a book. So Coffey set up a site on Canvas, the College’s online learning management system. There, students could find links to the interactive Digital Orozco website, which provides a 360-degree view of the mural’s 24 panels. They could also access supplementary materials on a variety of topics related to the mural, including papers and projects produced by students from Coffey’s classes.

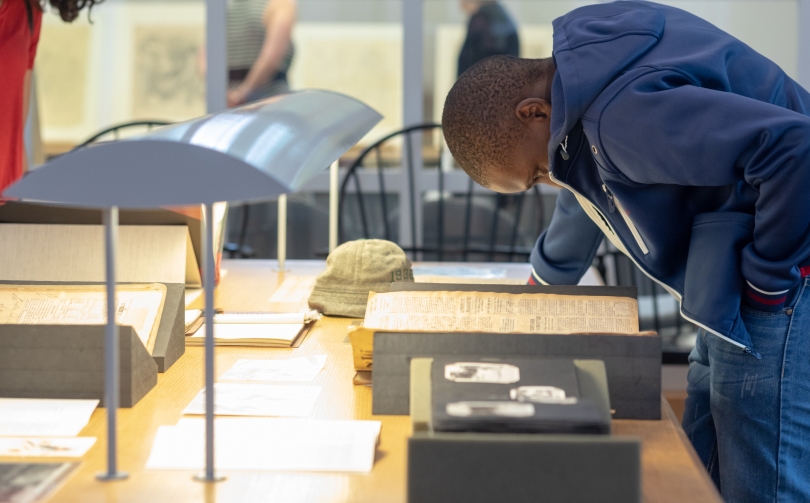

In addition to a discussion informed by questions Coffey posed to students in advance on Canvas, the ’22s participated in what Coffey calls a choose-your-own-adventure-like round-robin of activities: visiting the mural itself, where Coffey answered students’ questions; exploring archival documents about how people responded to the murals in the 1930s with staff at the Rauner Special Collections Library; looking at Orozco’s preparatory sketches and notes with curators from the Hood Museum of Art; and viewing a film about the mural’s key mythic figure, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl.

In short, it was an opportunity for students to discover some of the rich resources available to them at Dartmouth.

“There are not a lot of schools with staff dedicated to helping undergraduates do research with primary materials—where there are no firewalls against undergrads coming in. Here, it’s laid out before you,” Coffey says. In her classes and in many others on campus, she says, students are encouraged to do original research.

“You’re not reading a secondary text where somebody’s already interpreted those documents for you and making it feel like there’s nothing left to say. You can work with materials that are largely untapped. The students I’ve worked with who’ve done really independent things—they’ve found something weird, and they think, ‘That’s cool,’ and they go with it. It’s a big part of how we teach in art history.”

Coffey hopes students came away from the experience with a new appreciation for visual culture and for “the role of the humanities as central to a liberal arts education, with opportunities for students no matter what field they’re working in,” she says. “It’s emphasizing what’s unique about a liberal arts college—why it’s a valuable way of learning.”

Hannah Silverstein can be reached at hannah.silverstein@dartmouth.edu.