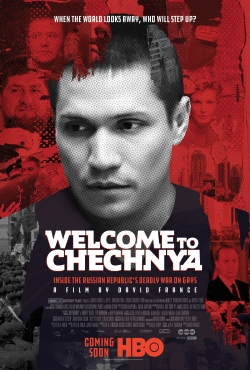

When the director of Welcome to Chechnya, a documentary about LGBTQ Chechens who face torture and death at the hands of their government, decided to digitally alter the faces of the film's subjects, he turned to Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences Thalia Wheatley to research the cognitive science of viewers' reactions to the doctored images.

Director David France needed to protect the identity of the people who were risking their lives to assert their LGBTQ identity, but he did not want the "face swap" technology to distract viewers from the story.

"This is what David France was really worried about, that they'd get it wrong and instead of empathy in the viewer, they'd trigger this uncanny, creeped-out feeling," says Wheatley, whose Social Systems Laboratory conducts research on the neuroscience and psychology of human connections.

Wheatley and graduate student Chris Welker, Guarini '24, showed more than 100 Dartmouth students four versions of a clip from the film with variations on the digital swap of actors' faces for the real-life activists. One version was a total swap of the faces, another version swapped the face but left the original eyes, another rendered the subject as a cartoon-like character, and one version was unaltered for comparison.

Because the privacy of the activists in the film was literally a matter of life and death, the students were asked to log on to a secure Dartmouth website and to complete a survey about their perceptions of the images in a one-time session.

What the researchers found surprised them. The full-face swap was consistently judged to be the most "natural" image. Wheatley, who has written about how the perception of a "sentient mind" is picked up when viewing a face, had expected that the clip that kept the true subject's eyes would be most effective at invoking empathy.

"Strangely, the full CGI face replacement seemed 'more real' than the version that left the person's eyes. Research has shown that the key feature in projecting the sense of a conscious mind is the eyes, so going in we expected that the image that allowed for the true expression of the subjects eyes would be the most relatable," Wheatley says.

But most of the student subjects responded that "something seemed off" in the combined version, Welker says.

"Our hypothesis is that you've got a mismatch here—the way the light hits the swapped face might be different from the way it hits the eye's surface for example—but there is something that doesn't seem quite real in a way that is not consciously perceptible," Welker says.

Based on this research, France entered the film, with the CGI full face replacement, in the Sundance Film Festival. This past January, it won the festival's special jury prize for editing. The film premieres June 30 on HBO.

For their part, Wheatley and Welker say a paper about their research for the film is forthcoming and they are exploring the possibility of pairing presentations of their research with screenings of the film.

William Platt can be reached at william.c.platt@dartmouth.edu.