My English Honors Thesis: Chapter Two

As I said in my first blog post, I am writing an English department honors thesis that views literature about drugs through the lens of German media theory. As of today, I've written about a hundred pages for it, and chapter two is pretty much done! Chapter two of my thesis is about a late nineteenth-century writer named Marie Corelli. Think of her as the Colleen Hoover of Victorian novels. She wrote tons of stuff, was incredibly popular, and was also hated by literary critics and devotees of "high literature." And, honestly, I cannot, in good faith, recommend her books to anyone. They're pretty bad. So why am I talking about her in my thesis?

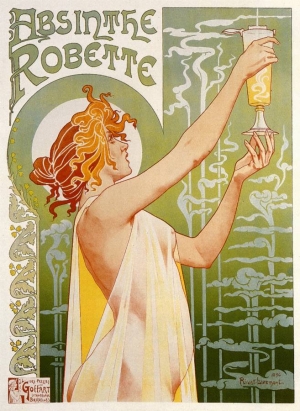

First, I should explain that I'm specifically talking about her 1890 novel Wormwood: A Drama of Paris, which follows a promising young man whose life is ruined when he becomes addicted to absinthe. Today, people can buy absinthe from a liquor store just like any other alcohol. And yet, absinthe was treated like an opioid or cocaine in Wormwood, and during the fin de siècle, people really believed it was a uniquely addictive and horrible alcohol, capable of causing hallucinations and degeneration. The reason? It has a special ingredient—wormwood—which we now know contains the compound "thujone." Absinthe was a fashionable drink in France during the nineteenth century, and as France suffered failures at home and abroad, absinthe was often blamed for ruining the population.

I read Wormwood for Professor McCann's senior seminar "Decadence, Degeneracy, and the Fin de Siècle" which was a super cool class about the late nineteenth-century artists known as the Decadents (think Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde) and contemporaneous anxieties about the fall of European societies. Corelli's Wormwood toes a fascinating line between decadence and anti-decadence—it's an aggressively moralistic book, and the author herself saw it as a warning to her fellow Englishmen and women to avoid the excesses of alcohol and opium. At the same time, it pulls heavily from both the decadent art tradition and absinthe advertising. Corelli's descriptions of absinthe hallucinations, for instance, have direct parallels both to De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and to the absinthe advertisements of her time. Although Corelli was immensely popular in her day, some reviewers even accused her of being a Decadent herself as a result of this book, and her own publisher found the material absolutely sordid. But it sold incredibly well. Corelli knew how to both harness the most compelling artistic trends of her day while also playing to her audience's expectations and desires for literature.

This brings me back to my initial question: Why am I writing about this book, if it's decidedly not High Literature? (Pun intended.) Something that the English department here does extremely well is allowing space for all varieties of English academia. Literary studies in its traditional sense, cultural studies, data-based textual analysis, close reading, historicism, media studies, comparative literature, and basically everything else can coexist in this department. It's a big tent. So you don't have to only focus on canonical works of literature, or even books at all. I am interested in Corelli because she was a massive literary force in her time—she was one of the first bestsellers at a time when the pulp fiction landscape was changing rapidly. Her literature may not stand the test of time, but that is all the more reason to pay attention to how she wrote, because it appealed to her contemporaries and therefore allows us to better understand how they thought of problems such as addiction, hallucination, and spirituality in the post-Darwin era. Think about it this way—if a scholar from the 22nd century wanted to understand the 21st century, they would not only need to watch the best TV shows and movies we produced, they would also need to watch the most popular ones, even if they were… not that great. After all, the "greatness" or quality of a piece of art is, paradoxically, both objective and subjective. How much someone gets out of a piece of art is a result of when and where they were born, their cultural frame of reference, and their taste.